A friend just asked me how hard it is to write grants and what is the format, so I have decided to post one of the bad ones I wrote years ago to give you an idea :) This is a rejected NSF proposal, but it gives you the idea of format to use. I hope it helps some :)

Paleo Grant Proposal.

Jason Lunze

Systematic analysis using stable C and N isotopes to better determine the possible interactions between the late Pleistocene and early Holocene populations of Homo sapiens and Canis dirus, Arctodus simus, Panthera atrox, and Smilodon californicus of late Pleistocene and early Holocene North America.

“Were these groups in direct competition for resources?”

(A yes or no question.)

I propose the question, “Were large predators of the late Pleistocene in direct competition for resources with arriving populations of Homo sapiens in North America?”

I propose that the problem of small sample sizes for the direct stable isotope comparison between early human populations and late large Pleistocene carnivores of North America can be overcome by comparing deposits of carnivore middens to human occupation and kill sites. In this not only can we determine the species by counting, but in the case of well butchered animal remains by humans that the C, and N values may be useful in comparing the proportion of distinct groups of primary consumers who were then consumed. This is useful as 1.) The extant amount of human bone material for comparison for this interval is negligible, 2.) The extant amount of bone material as consumed by both groups although somewhat less for the large carnivores is relatively abundant, 3.) Bones from both deposits may be fragmentary and hard to identify, and 4.) The types of isotope signatures for humans before and after the extinction event can be compared to those of the extinct carnivores to see if there decline was due to the disappearance of large herbivores presumed to be their obligate prey or the direct competition of humans who would have the same isotope signature after the extinction event. All material would have to be screened carefully and time averaged.

Research: Using Stable C and N Isotopes to Explore the Possible Interactions Between the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Populations of Homo sapiens and Canus dirus, Arctodus simus, Panthera atrox, and Smilodon californicus in North America. Were these groups in direct competition for resources?

Much research has been devoted to the decline and extinction of the North American megafauna. Three main causes for this extinction have been proposed. Firstly, that the extinction was caused by the peopling of North America by early Ice Age hunter gatherers. Secondly, that the extinction was caused by climate change at the end of the last ice age. Lastly, that disease may have been a primary contributor. Most studies concerning that the extinction was anthropogenic have focused on the interactions between large herbivores and the immigrating human populations (Martin and Klein 1984, and Koch et al. 1998). Little work has been done to examine the interactions between humans and large megafaunal predators.

I propose the question, “Were large predators of the late Pleistocene in direct competition for resources with arriving populations of Homo sapiens in North America?” The problem of small sample sizes for the direct stable isotope comparison between early human populations and late Pleistocene megafaunal carnivores of North America can be overcome by comparing deposits of carnivore middens to human occupation and kill sites. In this not only can we determine the species by counting as in previous studies (Mead and Meltzer 1985), but in the case of well-butchered and or small animal remains consumed by humans and predators that are not accounted for taxonomically can also be counted so that the C, and N values may be useful in comparing the proportion of distinct groups of primary consumers who were then consumed. This is useful as 1.) The total amount of human bone material for comparison for this interval is negligible (Leper 2004), 2.) The extant amount of bone material as consumed by both groups although somewhat less for the large carnivores is relatively abundant (Haynes 1984), 3.) Bones from both deposits may be fragmentary and hard to identify (Mead and Meltzer 1985), and 4.) The types of isotope signatures for humans before and after the extinction event can be compared to those of the extinct carnivores to see if their decline was due to the disappearance of large herbivores presumed to be their obligate prey or the direct competition of humans who would have the same isotope signature after the extinction event. All material would have to be screened carefully to positively identify consumption by either group and have good time constraints for comparison.

Intellectual Merit of Research: This study would be the first to examine if the populations of human hunter-gathers who crossed from Beringia were hunting the same prey as the Pleistocene megafaunal carnivores of North America. This is useful as it would show how the arrival of man may have directly affected the upper members of the North American food web, in contrast to the better studied effects on herbivores. This study would provide an isotopic signature for species which have not been characterized in previous studies as to their relations to their prey species during this geologic period and would better define the upper portion of the North American megafaunal food web.

Far Reaching Implications: The reconstruction of the interactions between Homo sapiens and Pleistocene megafaunal carnivores has modern impacts for reconstructing habitats for currently endangered species such as the modern Bengal tiger and grey wolf populations in developing and third world regions by giving a baseline for the overlap of predators and prey.

Introduction

It has been noted that there is a temporal correlation between the peopling of North America during the late Pleistocene and the decline of the North American megafauna (Haynes 1984). However, while there are many kill sites fossil human remains for this period are scant and much controversy surrounds them (Lepper 2004). No more than twenty sets of remains exist for the Pleistocene or early Holocene in North America (Bonnichsen et al 2005). Because the ages of these Paleo-Indian remains are controversial, as well as they are very rare and not easily accessible to study another method must be used to correlate their interactions with the large Pleistocene carnivores Canus dirus, Arctodus simus, Panthera atrox, and Smilodon californicus. One way to do this is to look at the specific trophic levels of the prey species they consumed.

This is complicated as it is hard to distinguish which faunal remains that were consumed by humans versus those brought in by other animals. A similar problem exists with the remains consumed by the large predators. This is enhanced for the predators because their faunal remains are preserved in a variety of settings (Mead and Meltzer 1985). At many excavated Paleo-Indian sites it is hard to distinguish between the two groups as well due to the presence of gnaw marks on apparent human kills (Fox et al 1992). A strict but comparable study group must be established before a comparison can be drawn.

These early human settlers are well represented by faunal remains from both Late Pleistocene and early Holocene sites. One Pleistocene and Holocene site in Pennsylvania, the Meadowcroft Rockshelter yielded 115,166 bones or bone fragments of which it is postulated that 7% were of Indian origin. These remains constituted a duration of deposition of roughly 10,000 yrs with some assemblages being pre-Clovis. The charred remains of toads, colubrid snakes, deer mice, and deer can be dated before 9,350 B.C. This may represent a faunal assemblage of predominantly small game for early humans at this local. However, at the Burnet and Hermits cave localities in New Mexico a large amount of large ungulate material is found in association with human artifacts from this period including Mammuthus (Mead and Meltzer 1985).

The first undisputed population of humans in North America belonged to that of the Clovis. Clovis artifacts are often found in association with Mammoth, mastodon, and other megafaunal remains (Fox et al 1992). They are also found in conjunction with small game. However, faunal remains are hard to specifically link to human consumption. At the Ryan Harley site in Florida, 368 bone specimens representing faunal remains were recovered, representing all five major classes of vertebrates, and evidence was given for the extraction of marrow from deer and alligator remains (Bonnichsen et al 2005). This can be seen as (figure 1). Once again while there are some remains which represent the megafauna, small game is heavily represented in the faunal assemblages.

Figure 1. Bonnichsen et al. 2005.

The Large Pleistocene carnivores Canus dirus, Arctodus simus, Panthera atrox, and Smilodon californicus are also represented by deposites of animal prey remains. As with those of human faunal remains it is difficult to link prey remains to specific predators. These predators also are represented in the fossil record by many depositional environments, around lakes, salt licks, dens, or general killsites. (Mead and Meltzer 1985). These remains are hard to distinguish from those of faunal remains butchered by humans (Fox et al 1992). An example of this can be seen as figure 2. This overlap implies some resource sharing even before an investigation is conducted, and helps vindicate a comparative study.

Figure 2. Fox et al. 1992.

The large canivores Canus dirus, Arctodus simus, Panthera atrox, and Smilodon californicus were cracking bones as human hunter-gathers were, this is evident in their tooth wear. The teeth of dire wolves from Rancho La Brae were found to have more fractures than contemporary wolves, a pattern which mimics modern hyenas and other large predator species which regularly crack large bones to extract marrow (Binder et al. 2002). Similar results were found for Smilodon (Naples 2002).

“The demise of the dire wolf and other large predators during the late Pleistocene may have been linked to the declining densities of large herbivorous prey and/or the inability of some specialized predators to switch successfully to smaller prey…Canis dirus probably sustained its large body size by selecting predominantly large prey in regions where it roamed (Fox-Dobbs et al. 2003, Anyonge and Roman 2006)”. The stable C and N values as examined by Fox-Dobbs et al. 2003 would indicate that this species of carnivore preferred prey species which were predominantly ruminants such as bison. Similar values were found for Smilodon (Fox-Dobbs et al. 2004).

There are also examples of large grazers which were predated by these carnivores, mammoth kills may have also have been scavenged as in the case of figure 2. There has been some speculation as to the mode by which the saber toothed cats took their prey. Lackey 2002 postulated that Smilodon may have been capable of taking down a full grown mammoth or mastodon in a group but probably was restricted to the calves of these species and smaller game. A similar conclusion was drawn by Naples in 2002. It is generally held by many authors that the short faced bear Arctodus Simus would have been capable of taking down most of the Pleistocene megafauna (Mead and Meltzer 1985 and Fox et al. 1992).

Methods: As can be concluded from the introduction a careful selection process must begin before any analysis of the stable isotopes of the faunal remains for the early hunter-gatherers and the extinct Pleistocene carnivores is to be performed. Both Fox et al. 1992 as well as Bonnichsen et al. 2005 have shown that it is often difficult to link faunal remains to predators. However, once again as the remains of both groups, especially those of Paleo-Indians are not abundant and readily accessible for study, the comparison of stable isotopes from the faunal remains of both groups is one of the only means to construct a comparison between these two groups.

To distinguish between the two groups a criteria for material to be studied from each must be established. The material to be studied from the human faunal remains will only be taken from site(s) which have well established radiometric dates for the purpose of comparison to temporally comparable carnivore remains. The sampled material will included as much material as possible, both identifiable taxonomically as well as that which can not be identified to eliminate any selective biases. The material will come from close contextual association with Paleo-Indian or Archaic Indian lithic artifacts. All material for the human faunal remains will exclude all material which has later gnaw marks from scavenging. Only those which have the green fractured nature as described by Bonnichsen et al. 2005 as shown in figure 1 will be included. Charred material from hearths will not be included to eliminate alteration to the Stable C and N ratios. A site(s) were an abundance of faunal material across the Pleistocene-Holocene megafaunal extinction occurred will be chosen to see if the isotope pattern changes after the extinction changes.

Material for the large megafaunal carnivores will be taken from a contemporaneous site isolated but within 50 km. of that of the human hunter-gather material, and must have a similar age of deposition. Accurate radiometric dates for these deposits are also important and must be within 1000 yrs. of the human site. An attempt will be made to determine the species of predator, where unidentifiable it will be assigned to be unknown but will be included in the study. Only material with clear gnaw marks as described by Fox et al. 1992 will be included in this group. Material which can be taxonomically identified will be included as well as bone fragments which cannot.

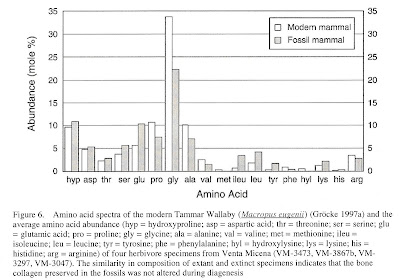

For both groups screening will be performed to verify that enough collagen for the stable C and N analysis is present. An example of the amino acid spectra necessary to draw this conclusion can be seen in figure 3. This is of concern for both the human as well as predator groups as the C:N ratio for the human faunal remains may be modified by cooking, and both have the possibility to undergo diagenesis which would as modify the results. Bones and bone fragments with unfused epiphyses will also be included in both groups to see if predation of immature prey was favored by either group. This may be important as adults are often the focus of large kill site faunal remains associated with humans (Mead and Meltzer 1985). Juveniles are associated with the Pleistocene megafaunal carnivores (Palmqvist et al. 2003).

Figure 3. Palmqvist et al 2003.

Once this is completed the C and N ratio will be plotted graphically for both the large carnivores and the human hunter-gatherer faunal remains. This data will include the standard deviation and error. These two groups will be plotted together so that a t-test can be performed to see if the groups are statistically distinct. The C and N ratios for the samples before and after the extinction for the human hunter-gatherers will then be plotted on a similar graph to see if there is any significant statistical difference in the ratio before and after. A sample plot of different species can be seen in figure 4.

Figure 4. Palmqvist et al. 2003.

Concluding Thoughts: Once the data has been collected and plotted some general conclusions can be drawn. If the C and N ratios for the faunal remains and the predators during the Pleistocene turn out to be statistically different as determined by the t-test than these groups may not have been in direct competition for prey resources. If they however group together than they may have been in competition for resources. This conclusion would be supported if the C and N ratios before and after the extinction for the human hunter-gatherer faunal remains changed as this would indicate that the Paleo-Indian population shifted its focus to other game after it out competed the predators by overkill. This may make sense as, “From the fossil record of their last 10,000 years, native Americans can claim to have lived benignly in their environment, neither causing nor witnessing many additional losses after the catastrophe of 11,000 years ago (Agenbroad et al. 1990)”.

References:

Agenbroad, L. D.; Mead, J. I.; Nelson, L. W. Megafauna & Man, Discovery of America’s Heartland. The Mammoth Site Hot Springs, South Dakota, Inc., Scientific Papers, Vol. 1. August 1990.

Agenbroad, L. D.; Barton, B. R. North American Mammoths, An Annotated Bibliography. The Mammoth Site Hot Springs, South Dakota, Inc., Scientific Papers, Vol. 2. December 1991.

Anyonge, W.; Roman, C. New Body Mass Estimates for Canis Dirus, The Extinct Pleistocene Dire Wolf. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol 26. issue 1, March 2006.

Bonnichsen, R.; Lepper, B. T.; Stanford, D.; Waters, M. R. Paleo-American Origins: Beyond Clovis. Center for the Study of the First Americans, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University 2005.

Delcourt, P. A.; Delcourt, H. R. Ecological Studies 63, Long-Term Forest Dynamics of the Temperate Zone. Springer-Verlag, New York, Berlin, Heidelberg, London, Paris, Tokyo. 1987.

Fox, J. W.; Smith, C. B.; Wilkins, K. T. Proboscidean and Paleoindian Interactions, Baylor University Press 1992.

Harris, J. M.; Jefferson, G. T. Rancho La Brea: Treasures of the Tar Pits. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 1985.

Haynes, G. Mammoths, mastodonts, and elephants. Biology, behavior, and the fossil record. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Haynes, G. The Early Settlement of North America, The Clovis Era. Cambridge University Press 2002.

Hoppe, K. A. Late Pleistocene mammoth herd structure, migration patterns, and Clovis hunting strategies inferred from isotopic analyses of multiple death assemblages. Paleobiology, vol. 30, issue 1, January 2004.

Kurten, B.; Anderson, E. Pleistocene Mammals of North America, Columbia University Press 1980.

Lepper, B.; Bonnichsen, R. New Perspectives on the First Americans, A Peopling of the Americas Publication 2004.

Martin, P. S.; Klein, R. G. Quaternary Extinctions, A Prehistoric Revolution, The University of Arizona Press 1984.

McAvoy, J. M. Clovis Settlement Patterns: The 30 year study of a late Ice Age hunting culture on the Southern Interior Coastal Plain of Virginia, Nottoway River Survey, Part I. Archaeological Society of Virginia, Special Publication Number 28, Nottoway River Publications, Research Report Number 1. 1992.

Meltzer, D. J.; Mead, J. I. Environments and Extinctions: Man in Late Glacial North America. Center for the Study of Early Man, University of Maine at Orono, 1985.

Merceron, G.; Zazzo, A.; Spassov, N.; Geraads, D.; Kovachev, D. Bovid paleoecology and paleoenvironments from the late Miocene of Bulgaria: Evidence from dental microwear and stable isotopes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Vol. 241, Issues 3-4, 14 November 2006, pp. 637-654.

Palmqvist, P.; Grocke, D. R.; Arribas, A.; Farina, R. A. Paleoecological reconstruction of a lower Pleistocene Large mammal community using Biochemical (δ13C, δ15N, δ18O, Sr:Zn) and ecomorphological approaches. Paleobiology, vol. 29, issue 2, June 2003.

Sellards, E. H. Human Remains and Associated Fossils from the Pleistoce of Florida. Doctoral dissertation 1913.

Spencer, L. M.; Valkenburgh, B. V.; Harris, J. M. Taphonomic analysis of large mammals recovered from the Pleistocene Rancho La Brea tar seeps. Paleobiology, vol. 29, issue 4, December 2003.

Zakrzewski, R. J. Biodiversity response to climate change in the Middle Pleistocene-the Porcupine Cave fauna from Colorado. Journal of Paleontology, vol. 79, issue 6, November 2005.